Try working backwards from the present day. It is more likely that recent records have survived and they will be easier to read and interpret. Make a note of whatever information you find out about your house even if it is not what you are primarily looking for eg listing owners and occupiers names at various dates may eventually help you to identify the right house in earlier archives which refer only to the owner/occupier and not to the property.

It is advisable to start with printed sources such as trade directories and books on the history of the area, if only to get some background information. These may indicate which parts of a town were developed first. Look at the property itself and note any evidence of architectural styles and subsequent alterations.

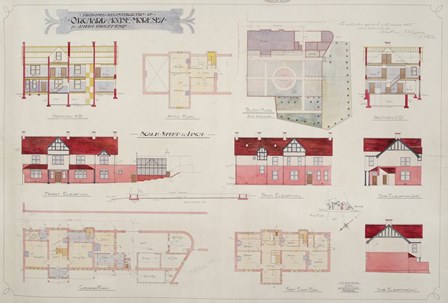

Maps, Plans and Sales Particulars

By comparing a series of maps, you may be able to work out or narrow down the date your house was built and you should also be able to see whether any major alterations have been made.

These records were created under the Finance (1909-1910) Act. The Act provided for the levying of various duties on land ('rates'). Every piece of property and land throughout the whole country was inspected by the Board of Inland Revenue's Valuation Office. The chief duty to be levied was the Increment Value Duty. House owners with land of less than 50 acres and worth less than £75 per acre were exempt.

Each property or parcel of land is indicated on the valuation maps (based on the 2nd edition, 25" OS sheets) by an assessment number and the boundaries of each property are marked in red. These numbers reoccur in numerical order in the valuation books, sometimes known as the 'Domesday Books'. They contain a brief description of the property and its address, plus the names of the occupiers and the names and addresses of the owners. Where land is involved, its estimated extent is mentioned.

These are important sources for architectural style and interior layout, and they often show the building in elevation. They may name the architect or building and provide an approximate building date. They are the result of 1858 Local Government Act and the 1875 Public Health Act, which gave urban and rural authorities the right to make bye-laws regulating the structure, stability and positioning of buildings.

Building inspection plans can be found in the collections of most of the pre-1974 rural and urban district councils in Cumbria. Some architects firms have deposited their working plans in archive centres. Please check with the relevant archive office for details or search CASCAT Cumbria's Archive Catalogue.

From 1841, and every ten years thereafter, the census contains house by house details of family groups. The most recent one available is the 1911 Census. Information includes all the members of the household and their relationship to the head of the household, ages, occupations and place of birth.

It may be possible to narrow down the age of a 19th century house by seeing what date it first appears on the census. One of the best uses of the Census is to flesh out the property history with details of those who lived in the house and the way they lived.

These are annually published lists. The information in electoral registers includes the name and address of the person who is entitled to vote.

When property qualifications were applicable, the name of the qualifying property was often included.

Electoral registers are arranged alphabetically according to the surname of the voter until Autumn 1920. After that street names are listed alphabetically within each township and the voters name appears alongside the number of his house within that street. They can help to track both owners and tenants, providing they were registered. It is worth remembering that many men could not vote until 1918 and only married women over the age of 30 and with property could vote from 1918 onwards. Women were not able to vote on the same terms as men until 1928.

Produced from circa 1770 onwards as land which had previously been common or waste was taken into cultivation, the maps show the land which was to be enclosed and the accompanying awards record how much land was allotted and to whom. As such, these records are really concerned with land, not buildings, but quite often they do show buildings, particularly if the common land was close to a town or village.

They give owners' names, field boundaries, etc. However, they do not include land enclosed at an earlier date and so rarely cover village or town centres. Most were made at very large scale. They are accompanied by a handwritten copy of the award which contains a schedule of what former common land was allotted to which landowner. In addition, the award may also record boundary obligations, the setting out of public and occupation roads and the sites of public quarries and watering places. A complete list of Cumberland enclosure awards is available to view on CASCAT (series reference Q/RE). Please note there are few areas of Furness covered by Enclosure.

Landowners needed accurate information about the boundaries, area and land use of their estates. 19th century plans are especially common but it is possible to find examples dating back to the 16th century. These large scale plans can record landownership, boundaries, field names, land use, tenants. They may give pictorial representations of the buildings which need to be interpreted with care.

Lords of manor rented out houses and land to their tenants in return for rent or labour services. Every time there was a transaction involving a copyhold property it would be entered (i.e. copied) in the court rolls. The tenant would appear at the manorial court and surrender his property to the lord, whereupon a new tenant would be admitted. The documents are often listed as "Surrenders and Admittances". Admittances rarely describe buildings in detail. The documents include details of the parties involved and a description of the property. This can sometimes include details of neighbour's property and of all the buildings etc attached to the property. Tenants may also be presented in the manorial court for allowing houses to fall into disrepair or for using the lord's timber for repair work without permission. Surveys of the manor usually describe the manor house in some detail. Rentals list tenants, property and rent paid.

The Manorial Documents Register for Cumberland, Westmorland and Lancashire can be searched online.

The 6 inch scale dates from circa 1860 for the former counties of Cumberland and Westmorland and c.1850 for Yorkshire and Lancashire. These maps are especially useful if you are searching a wide area for a particular property. They usually name important buildings and isolated farmhouses but they only show built-up areas in a rather generalised way.

25 inch plans date from circa 1860 for Cumberland and Westmorland and from the 1880s for Lancashire and Yorkshire. They are amongst the most detailed and accurate plans available to us. Buildings are mapped individually and prominent buildings are named. The first edition is hand coloured (carmine for brick or stone buildings, grey for wood or iron).

Towns with a population of over 4000 were surveyed at a scale of 10.56 feet to the mile in the 1860s and 1870s. These plans show immense detail (sometimes even the internal layout of buildings).

Ordnance Survey maps for Cumberland were published as follows:

- 1st edition 25" scale, c.1865

- 2nd edition 25" scale, c.1900

- 3rd edition 25" scale, c.1925

OS maps do not record ownership or occupation. Reference books to the 1st edition give brief descriptions of areas shown on the maps (acreages, land-use).

In 1538, an order was passed that registers of baptisms, marriages and burials had to be kept. In reality few survive from this date. The information they contain may include the abode of the people in the entries. If the name of the property you are researching is included it may be possible to trace it back to the date the registers begin. Unfortunately sometimes the name of a hamlet or group of houses may be all that is given. This does indicate that there was someone living in the same place as the property you are looking for even if it is in a different building. In later registers (post 1813 for baptisms and burials and post 1837 for marriages) a printed form is used and a more precise address is often given.

Wills were proved in the church courts until 1858 and in the civil probate registries thereafter. They usually contain bequests of real property although they rarely describe the property in detail.

Probate inventories (late 16th-mid 18th centuries): Before the probate court allowed the distribution of the effects of the deceased it required an inventory to be made of his/her personal belongings. Inventories describe and value the belongings of the deceased, often room by room. Researchers can use probate inventories to deduce the number and size of rooms and find out about furniture, clothes, etc.

Probates and inventories for the Cumbria area are available at Carlisle Archive Centre or Lancashire Record Office in Preston.

19th century rate books often survive; examples can be found dating back to the 17th century. They name owner and occupier, describe the property, give its location and its rateable value. If the rateable value has increased, this might suggest that the house has been enlarged or improved.

Personal account books of property owners, account books of craftsmen and builders, vouchers, receipts, etc. may give details of building or repair work including materials used, costs, etc. It is worth putting the address, street or owners' names into CASCAT to see what records are available.

From around 1850 onwards, sale particulars were drawn up to attract buyers and provide them with details about a property. They often include elevations, photographs, room descriptions and plans of the house, grounds and estate. They may even give the date or era in which the property was built.

Land tax returns:

These were created between c1692-1832 and include tax paid by all but the smallest proprietors and often details of occupiers. Most survive between 1780 and 1832 when duplicate copies were kept with the Quarter Sessions records. The returns contain names of owners and occupiers and amounts paid. Unfortunately the property name is not always given so they are of limited use to property historians.

The returns were also used as proof of entitlement to vote. They rarely refer directly to the property assessed.

Hearth tax returns:

Between 1662 and 1689, householders paid a tax on hearths or chimneys. The returns record the head of the household and the number of hearths in the house (but not the name of the property). Hearth tax returns can be used to judge the relative size of a house. In conjunction with other records, they can help to identify houses. The originals are held at The National Archives but copies and transcripts can be found at the Carlisle, Kendal and Barrow archive centres.

Records produced following the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836. Tithes were a type of church tax which since the Middle Ages had been levied on the inhabitants of a parish for the maintenance of the church and its incumbent. Farmers had to offer a tenth of their harvest while craftsmen had to offer a tenth of their wares. After the Tithe Commutation Act the payment of tithes was replaced by a rent charge apportioned on landowners according to the value and acreage of their lands.

Tithe maps and the accompanying apportionments (usually called awards) show the land of the parish divided up into plots. Each of these plots is numbered and the names of the owners of particular plots are set out in the tithe award. You can discover the amount of land associated with a property, the name of the land owner, tenants (if different), field names and boundaries and the extent of particular estates. The reliability of these plans varies and they omit any land not previously subject to tithes. A complete list of Cumberland tithe maps and awards can be seen on CASCAT (using the series reference DRC/8). The Dalton-in-Furness tithe map covers all of Barrow, Walney and Ireleth.

The deed should describe the property being sold, leased or mortgaged. This description may be detailed and helpful or infuriatingly vague. In some types of deed the property description is stylised and conventional. Sometimes the description was copied from an earlier deed and not updated. In order to prove the vendor's right to sell, deeds often refer to earlier transactions.

The endorsements made on the outside of the deed will state the type of deed, the parties' names, the property and the date.

With practice, it is possible to separate the historically important information from the legal verbiage. "Bargain and sale" and "lease and release" are names of earlier forms of conveyances. The date and parties are followed by a recital of earlier related transactions introduced by the emboldened "Whereas". To find details of the property, look for the emboldened "Witnesseth" and then (a few lines further on) "All that Messuage…". Exceptionally, some deeds may include site plans of the property in question.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries a number of large scale plans of towns were published by professional cartographers. These often provide an accurate record of the development of towns and buildings prior to the commencement of the Ordnance Survey in 1865.

The mapmaker John Wood produced maps of Carlisle (1821), Whitehaven (c1820-30), Penrith (c1820-30), Wigton (1832), Cockermouth (1832) and Ulverston (1832). W Mitchell surveyed Maryport in 1834. A detailed map of Brampton was produced for the Earl of Carlisle in 1777, and Andrew Pellin drew the earliest known plans of Whitehaven in the 1690s.